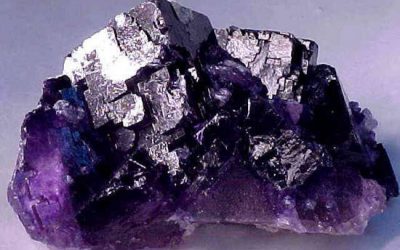

Flourite or flouspar is the mineral form of calcium fluoride, a commodity chemical used to produce a wide range of materials.

This case study, conducted by Coast Rights Forum (CRF) in collaboration with KeNRA, highlights the impact of the Kenya Fluorspar Company (KFC) on the people of the Kerio Valley in Elgeyo Marakwet County of western Kenya. The study examines KFC’s Kimwarer mine at two locations – Soy and Chemoibon – which are near Kimwarer town in Keiyo South constituency.

Part of the Rift Valley, the Kerio Valley, which ranges from 1,200 metres to 1,000 metres deep, is known for its significant fluorite deposits discovered in the 1960s. Fluorspar, the second most important mining commodity in Kenya after soda ash, is used to produce fluorites, which are a key component in the manufacture of industrial commodities such as steel, hydrofluoric acid and fibreglass. KFC, established in 1971, is based at the southern part of Kerio Valley in Kimwarer town and is one of the few large mining companies in Kenya. The company exports most of its produce to Europe and India.

Once a government business, KFC was privatised in 19973 and is chaired by Charles Field-Marsham,4 a Canadian who is also the son-in-law of Nicholas Biwott, the former MP for Keiyo South (1979 –2007) and cabinet minister who served as right-hand man to President Daniel Arap Moi. In April 2015, cabinet secretary, Najib Balala, said the company had revenues of around KShs 4-billion a year, but had declared only KShs 300,000 to the government.

KFC plays a significant economic role in Keiyo South and is the only major employer there. It employs around 200, people, most of whom are from Keiyo district. The company reportedly paid Keiyo county council KShs 18.4-million a year in land rates in 2012, and also pays local carriers millions of shillings a year to ferry fluorspar from field to factory.6 However, these positive local impacts must be weighed against the experiences of many others in the local community.

The problem of historical compensation

Mining by KFC is controversial because of the unresolved issue of compensation for loss of land going back to the 1970s that continues to affect the local community and blight relations between it and the company. In 1973, the government set aside 9,070 acres (3,664 hectares) of land used by the local community for the KFC; according to government sources there were 4,379 people living on this land who were entitled to compensation. However, the sum offered for the loss of land was paltry – KShs 450 per acre – and was rejected by the overwhelming majority of villagers. Only a small number of villagers accepted compensation (209 people, according to the villagers’ information) but the government now claims that compensation has already been provided for all. Indeed, the government set aside a sum of KShs 3.6-million for compensation in 1975 but most of this disappeared, presumably to corruption. Ever since, the villagers have been campaigning for fair compensation and are now organised in the Kimarer Sugutek (Fluorspar) Community Trust, established in 2005. In effect, the villagers live as squatters on ‘their’ land. Estimates are that around 1,500 families living in the mine area farm an average of around 4 acres of land.

In 2009, the villagers tried to take their case for compensation to the Kenyan High Court in Nairobi, but this failed to progress due to lack of funds. In 2011, the villagers presented a memorandum to the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission in Nairobi and Eldoret, but the Commission failed to mention this in its final report. The Community Trust says its meetings in the local area are often disrupted and frustrated by powerful local leaders, the police, provincial administrators, and the KFC. Some community leaders have even been arrested or persecuted.

This situation is bad for both the villagers and the company: the villagers are frustrated at remaining squatters in an uncertain situation, while the KFC is annoyed at not being able to freely engage in mining activities on the land and has long implored the government to remove the ‘squatters’ from ‘their’ leased land. In 2012, for example, KFC’s managing director wrote to the Commissioner of Mines and Geology to undertake ‘urgent action’ against 2,500 to 3,000 people in the area and livestock which were moving freely and interfering with KFC’s work.

In May 2015, the government announced it was setting up a taskforce headed by a lawyer, Paul Otieno Nyamodi, to investigate concerns raised by the local community.7 Five members of the local community will participate in this taskforce.8 According to the government statement announcing the taskforce, the latter will ‘explore ways of compensating the residents for their deprived land’ [sic] and also ‘investigate circumstances under which compensation alleged funds [sic] were diverted to other uses by past and present administrators and politicians’.9 However, in addition to historical compensation, the Community Trust has a long list of grievances against the KFC for a variety of adverse impacts on their livelihoods.

Other adverse impacts of mining

The company is in effect pressing the local community to relocate without offering fair compensation or the means to rebuild their livelihoods elsewhere. The Community Trust says that when the KFC wants to expand mining to a new part of the lease area where villagers are living, it induces them to move with the offer of KShs 15,000 (US$144), a sum regarded merely as a ‘token’ by the villagers. If they refuse, some people’s houses have been demolished while others have either been forcefully evicted or engulfed by mining operations, leaving them no choice but to leave.

People are also not allowed to rebuild or make significant renovations to their homesteads located within the lease area. Erecting a fence around the homestead or making improvements to the traditional mud thatches by introducing iron sheets can result in warning letters being issued. The Community Trust states that the company has: continued to disturb our people and disrupted their livelihoods and in the process have suffered dire social and economic inconveniences and losses as well as mental anguish and trauma due to these haphazard mining plans. KFC mining operations thus further contribute to the issue of Internally Displaced Persons within the lease area.

KFC does not allow people in the lease area to grow food and cash crops on their land. If farmers try to prepare their land for crop planting the KFC plants trees, so to all intents and purposes evicting the farmers by depriving them of their livelihood. Some women farmers say that in order to farm they have to leave their homes in the leased area and travel long distances, which means leaving their children without care. Women then face the added burden of having to transport their yields back to where they live.

Similarly, the company does not allow people in the lease area to harvest their trees as logs, timber, firewood, or charcoal, which could also provide an important source of livelihood. Women caught looking for firewood can be arrested and their firewood and tools (pangas, axes, and ropes) confiscated by the KFC guards, the Kenya forest guards, or the police.

Local villagers believe local water supplies may be polluted by mining activities; if independent water sampling has taken place, the villagers are unaware of it. They say that KFC discharges effluents from its processing plant/factory into the Kimwarer and Mong rivers which join to make the greater Kerio River or Endoo. The local residents use the water from these rivers for drinking, watering their livestock, and irrigation. Kerio River also serves Elgeyo Marakwet, Baringo, West Pokot and Turkana counties. Media reports from as long ago as 2004 claimed the company was releasing waste laced with hydrochloric and sulphuric acids and other heavy metals into the river, posing risks to the lives of the people using the water.

A Ministry of Water and Irrigation investigation in 2005 found that waste-water from the company’s sedimentation ponds, which had high levels of fluoride, were finding their way into the Kimwarer River. The report noted that KFC ‘is likely to be releasing the waste direct to the river’, and called on the company to desist from doing so, stating ‘the rights of the locals have to be respected’.

The company uses heavy mining machines in areas where landslides, soil flow, and rock falls often occur, which endanger the lives of people and livestock as well as buildings and crops. There have been cases where people’s goats have been buried alive by the company’s bulldozers and livestock run over. These machines also uproot and bury indigenous trees which have economic, cultural and medicinal significance. The villagers are never compensated. These mining landslides, soil flows, and rock falls have also blocked and destroyed waterways and water pipes, affecting the community’s access to water. Yet KFC has not, as far as is known, offered to supply alternate sources of water to the local community.

KFC mining operations have created large quarries and pits that endanger the lives of people and livestock. A number of cattle, sheep, and goats have fallen into the open quarries and died or had their limbs broken. The community is unaware of any case of compensation for any livestock deaths or injuries caused through such accidental falls. The company also uses powerful mining explosives that cause huge, loud explosions, and throw stones, rocks and other debris which have sometimes hit or killed animals or damaged nearby buildings and crops, and endanger people’s lives.

KFC has established road barriers in a number of places13 which are guarded 24 hours a day where company security guards check incoming and outgoing vehicles for ‘security’ purposes. However, the guards also harass local traders selling charcoal, firewood, timber, and poles. The KFC guards sometimes hold a truck load of these goods for hours or even days without reason even when the traders have permits and the items do not come from the lease area.

The police post at Chebutiei mainly serves the interests of the company rather than the local community by arresting people who are perceived to have wronged the company. In 2013, for example, four men were arrested one night and arraigned in Eldoret Law Courts on charges of theft for resisting tree-cutting in their village by KFC employees. The police who patrol the area are seen as working for KFC and the people regard the local government as simply siding with the company.

The KFC’s mining operations destroy graves through the use of heavy and earth-moving machines. However, the government has not asked the company to put measures in place for the exhumation and reburial of the deceased relatives. The local community regards this as a distinct lack of respect for those departed. The Community Trust notes: the KFC has earned a reputation of a hostile neighbor that looks down upon our community and does not have any respect for us and our departed brothers and sisters, our cultural beliefs and practices, the rule of law and good neighborliness.

In light of these extensive problems, KFC’s local community development spending is hopelessly inadequate. In Chepsirei village in Chop sub-location, however, local people have praised the company for the maintenance of the local road and for building classrooms in various schools in the area.

Article courtesy of http://ianra.org/